A Summer of Archives

Reclaiming Memory: Collective and Personal Histories Through Family Photographs

When I was nineteen, I discovered the photographic archive of my family. The boxes containing messy piles of pictures were hidden in the closet of my parents’ house, for some reason never properly catalogued. We had our much better-preserved family albums, from the year I was born until around five, and for whom I’ve always had a fascination. In fact, as a child, my mom often found me sitting in the hallway beside the sideboard where the albums were stored, spending hours immersed in the pictures. I had no idea there was another photographic archive. When I stumbled upon it at the end of my adolescence, in the middle of the pandemic, and right at the beginning of my journey as a photographer, it was like a revelation.

This discovery marked the beginning of my project “Il dilemma del porcospino” (“The hedgehog’s dilemma”), which became my second self-produced zine in 2020. In this project, I merged self-portraiture with found family photographs, starting from the discovery of the previously mentioned forgotten boxes.

Now, five years later, I’ve made the unusual decision to return to it and work on a second edition. This time, I’m delving deeper into archival photography and connecting the process of critically looking at family photos to the reappropriation of my origins and the re-narration of Southern Italy. After all, my artistic practice has always been a natural repetition of the same need to go deeper into certain aspects of the human experience.

At the time of the first edition, I wasn’t familiar with the term vernacular photography and wasn’t fully aware of the value it holds for the practice of many photographers and artists. These photographs allow for a reclamation of stories often left out of dominant narratives, opening space for marginalized voices, domestic experiences, and intergenerational memory. Just as history is never entirely objective, neither is personal memory. It's refracted through emotion, perspective, context, and silence. Family narratives are even more involved with the internalization process, and listening to the gaps that have been left behind, to spaces open to interpretation, makes art even more interesting, blending objectivity with something that stands much more ambiguously.

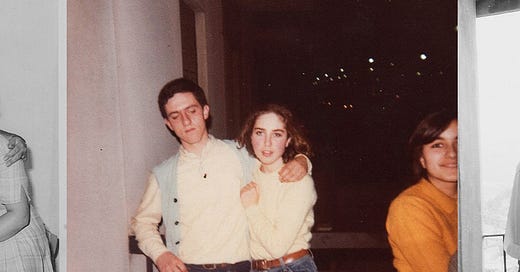

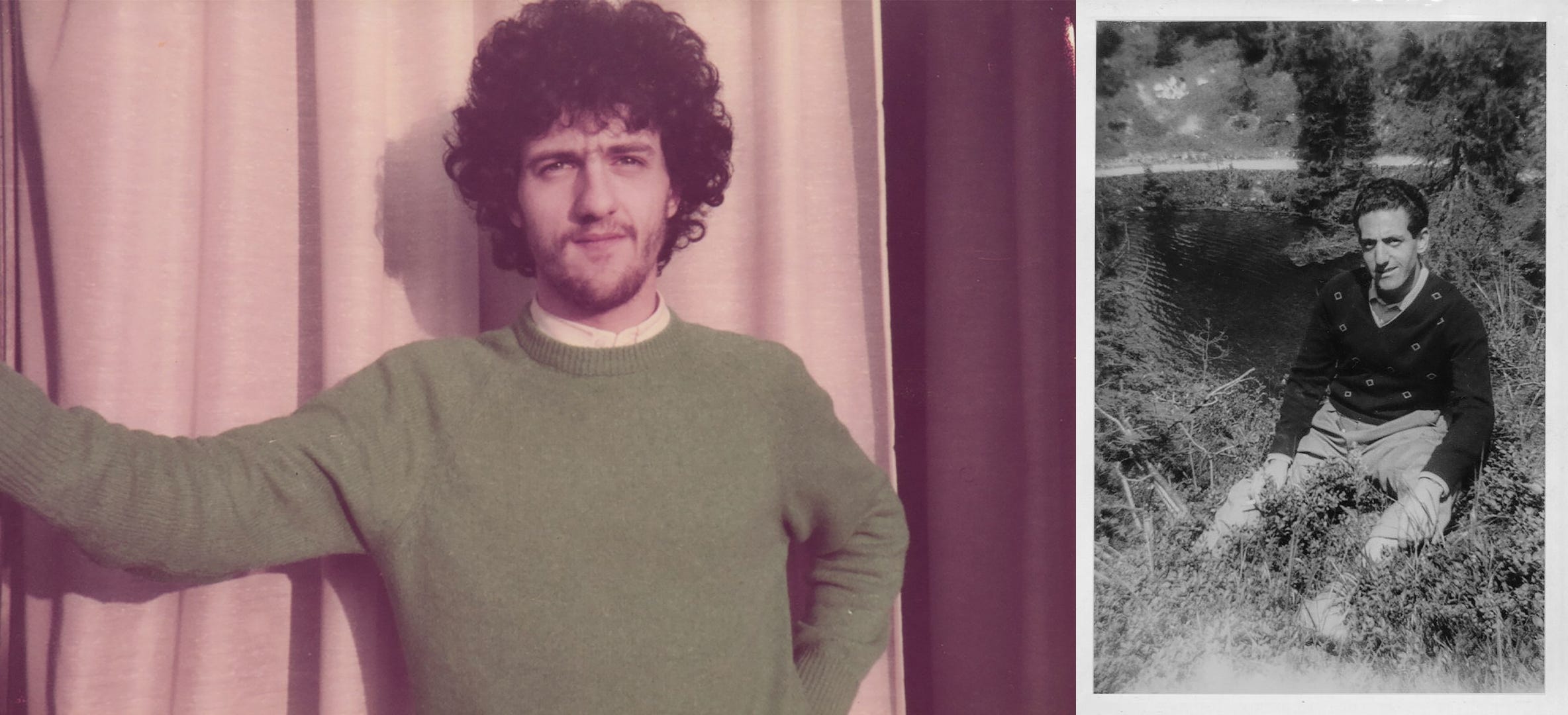

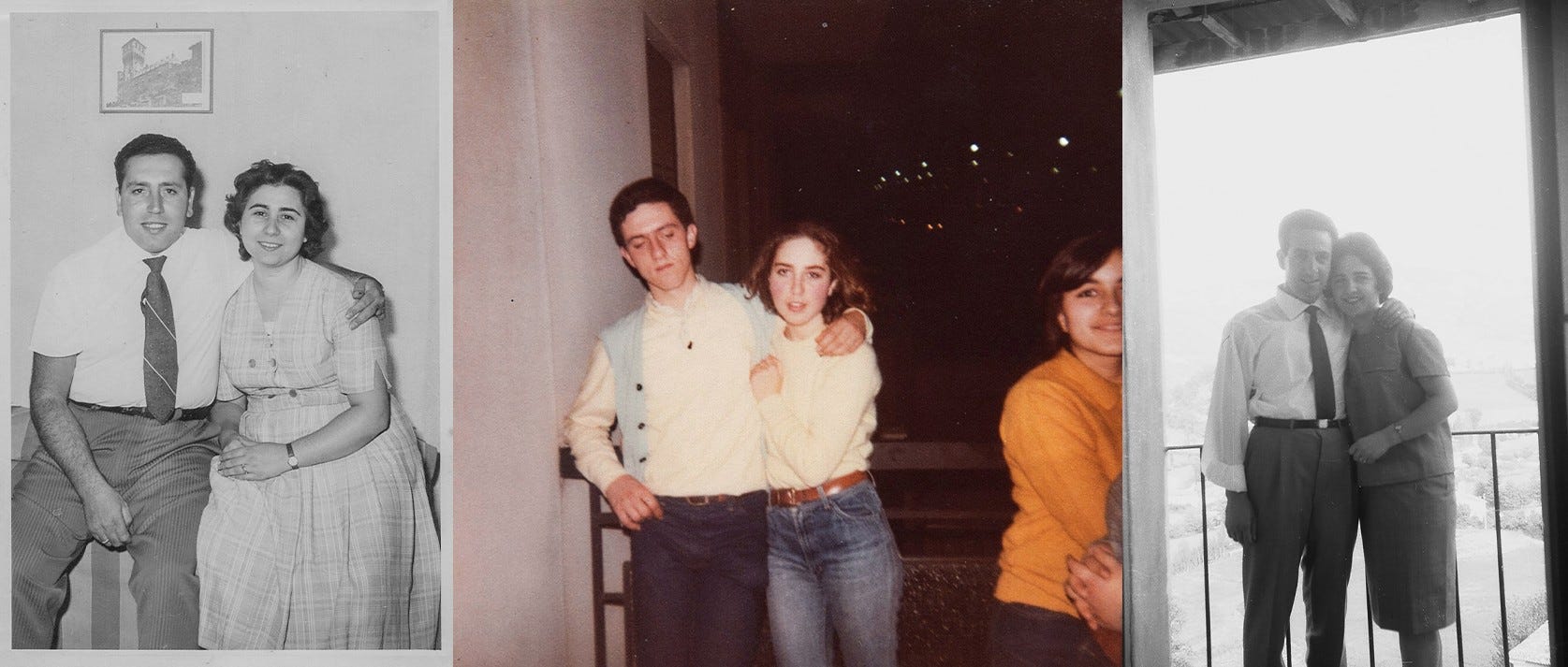

The photographic archive of my family dates back decades before I was born, starting with my grandparents in Sicily when my parents were younger, then my parents when they met. What struck me was a sense of repetition, a strange mirroring posture that seemed like a play of some social-relational dynamic, probably triggered by the presence of the camera. I think lots of family archives have resemblances, but to me, it was a discovery to see the whole history of my family unraveling before my eyes in a way that their storyline seemed already written.

I witnessed firsthand how going through the family archive means confronting a past I wasn’t a part of, yet I’m entangled with. I had feelings of estrangement and belonging, and many questions about how I subjectively interiorized my familiar history.

“Il dilemma del porcospino”, inspired by Schopenhauer’s titular metaphor, started as an exploration of the fragile balance between proximity and distance in human connections. However, there’s a more personal reason why this project was born and in the end, it’s a story about my life. I longed for connection, but I kept repeating familiar patterns that felt rooted in a past I didn’t quite know yet.

Intertwining my grandparents’ and parents’ lives with mine appears to me, especially five years later, as an open-ended confrontation with memories from my childhood and conflicts with my family, with an intention of learning to live in the complexities.

Through conversations with my parents and relatives, I learned about my great-grandparents and grandparents’ lives during World War II in Sicily. I heard about trauma and mental health struggles that, at the time, had no language — referred to only as u mali (“the evil” in Sicilian), something unspeakable, especially for men, who also had to face the burden of compulsory military service at 18.

The stories that stayed with me are particularly the ones that involve the women of my family, who, in their own way, all made acts of emancipation in a deeply patriarchal environment. My maternal grandmother, Laura, was one of the first women in Sicily to drive a car, all while being the caretaker of the family and the housewife. My paternal grandmother moved from a tiny village of hundreds of people in rural Sicily to pursue an education and become a teacher; in adulthood, she was a working single mother of three because of the relocation of my paternal grandfather, which resulted in a long-distance marriage in the broaded context of the forced migration that hit Southern Italy in the 1950s.

One picture, depicting my mother at around 15 years of age, shows her standing in front of a wall in her old neighborhood, with the same haircut I now have myself. Barely visible on the right, there’s graffiti saying, “Morte al fascio” (“Death to the fascist”), a small, accidental detail that keeps resurfacing in my memory and feels emblematic of an unspoken resistance, of something shared between generations.

Something I noticed while going through the archive is how drastically the landscape has changed, depicting an almost unrecognizable island coming out of the war, soon to face one of the darkest chapters in Sicilian history, with the mafia infiltrating public institutions. And yet, despite the abuse and transformation, the island remains the same in its spirit.

Perhaps this is what links this intimate project to the broader story of my island. A deep-rooted desire for freedom and resistance, something woven into the island’s history and somehow transmitted to its inhabitants, a trait that feels impossible to eradicate.

This summer, under the scorching temperatures, I find myself once again surrounded by photographs — scanning, selecting, questioning, and recontextualizing. Summer is a complicated time for me; it’s deeply transforming, but it also erodes my body and soul. The days are thick with heat, chaos, and overtourism. There’s a collective need to retreat, to find slower rhythms that feel more honest, more bearable.

In this sense, going through the archives feels like an act of resistance — quiet, focused, and deeply rooted. It’s a more sustainable way of being present in this land: staying inside with old photographs instead of consuming, looking inward instead of rushing forward. Revisiting this work now, five years later, isn’t something artists often do, but it’s important for me.

It’s not just about finishing something I started; it’s about asking how the questions have changed, how I’ve changed, and how this place continues to shape that process. In doing so, I see an opportunity to move beyond the comfort of hindsight and experience, while still honoring the person I was then and preserving the intentions that shaped the work in the first place.

Finally, here’s a recap of recent things I’ve been doing outside mainstream social media and ways you can support my work offline.

To support the second edition in the making of “Il dilemma del porcospino” consider one of these ways HERE

I’m co-curating the next collective book published by Ephemere with the title Duality. More info HERE.

My book Born from salt (Japanese Edition) published by Ephemere is available at $27.00 + shipping HERE.